Jaala Pulford is strong as steel.

Forged through 12 years as a union organiser, honed by 25 years of political activism in the Labor Party. A newly-minted Minister of the Crown.

But on this day, she barely finds the strength to ask the doctor how long her critically-ill daughter Sinead has left to live.

“He said, ‘why don’t you tell me how long you think she’s got’,’’ Jaala recalls.

“And I said, ‘weeks?’ I was fairly tearful at this stage. ‘Is it weeks?’

“And he shook his head and he said ‘no’.

I said ‘is it months?’ And he shook his head and he said ‘no.’

“I said ‘is it days?’ And he said ‘Yes. It’s days. You need to take her home now so that she can die.’’

Sinead Pulford passed away six days after that conversation, at 5.15am on Friday, December 12. She was 13 years old. She would never grow up to be a circus performer.

It was 13 days after the Victorian state election. Her mother had been Agriculture and Regional Development Minister for just one day.

Numbers. Jaala Pulford’s life revolved around them as her daughter’s illness ran parallel with the Victorian election campaign.

At home. The pain, how bad was it on a scale of one to 10? The tumours, how many of them?

At work. How many votes did she need to hold office? Would Labor win enough to tip the Coalition from office?

And as her personal and professional worlds collided: how many seats would she need at Government House for her family to watch as she was sworn in as Minister?

Four, or three?

The year 2014 started well in the Pulford household in Ballarat.

Sinead, 12, was enjoying year 7 at her new school, Ballarat Clarendon College. She was immersed in homework, sport, trips, after-school activities.

She mentioned in mid-August she had a sore back, but the family put it down to her sleeping on the floor for 48 hours to raise money for children in Africa. And it took more than a stiff back to slow Sinead down. She kept jumping out of trees onto the caravan roof, honing her skills on her beloved unicycle in hope of a career as a circus performer. Juggling, stilt-walking.

“She was not a girl who liked to sit around and talk about boys and nail-polish,” Jaala recalls. “We used to take that unicycle everywhere.’’

On September 12, Jaala’s husband Jeff took Sinead and her brother Hamish, 10, away to Bali with some family friends for a couple of weeks. Jaala stayed home. The state election was looming and everyone in state politics was working hard.

For Jaala, who joined the Labor Party at 16, worked for 12 years at the National Union of Workers, and had been elected to Parliament eight years earlier in the Upper House seat of Western Victoria, it was a hugely exciting time. Labor was a chance to beat the Napthine Coalition Government after just one term. Jaala felt she’d worked towards this moment all her adult life.

The Pulford kids had a great time in Bali. On September 18, Jeff took them to an elephant park. Sinead was called out of the crowd to help the animals with maths tricks. Then she spent three fun-filled hours in the swimming pool with Hamish and the other kids.

“Her last good day was a really good day,’’ Jaala says.

But later that afternoon, Sinead told her dad she had a lump in her tummy. Jeff sent a text to Jaala to let her know, and organised for a doctor to come to their villa in Ubud.

The doctor came, looked, and suggested they go to the international medical clinic in Kuta.

A general doctor and four specialists examined her. Jeff, now becoming seriously worried, was taken into a room where a “distressed ‘’ oncologist told him to get home to Australia. Straight away. Sinead may have liver cancer.

Jeff called Jaala in her Parliament House office in Spring St. She tried to stay calm by focusing on logistics: get her family home. Book the hospital.

Inside, her world was falling apart. “I felt like the floor was falling out from under me,’’ she says.

On a video call from the airport, Sinead seemed tired, but okay. Jaala tried to stay positive. “It didn’t occur to me for a second that she would be dead three months later.’’

Jeff, Sinead and Hamish touched down at Melbourne Airport at 6am on September 20. Jaala’s dad took Hamish, while Jaala, Jeff and Sinead went straight to the Royal Children’s Hospital.

It took about a week to confirm Sinead’s diagnosis. She had, essentially, an adult cancer, not the usual childhood cancers (blood, bone and brain).

The shell-shocked family drove their little girl home to Ballarat while plans were made to start chemotherapy to fight the cancer invading Sinead’s body.

But she was unable to keep her pain medication down. Jaala put her daughter back in the car and drove down the highway, back to the RCH. “I couldn’t get a park outside the ED so I carried her in, she weighed 40 kilos, I carried her a short distance from the car park.

“She was in a lot of pain, an immense amount of pain. They always asked her to quantify it out of 10. That was one of the only times, maybe even the only occasion, she described it as 10.’’

Scans. Tests. More tests. Treatment plans. The RCH would become their second home.

And, much too soon, the gentle but devastating revelation that treatment would be palliative.

Struggling to understand exactly what was happening to her daughter, Jaala asked the doctors to put it in adult terms. What would it mean if she, as a reasonably healthy 40-year-old, had the same cancers?

“They said to me: ‘we would suggest to you that you have nine to 12 months to live and you need to get your affairs in order.’’’

Jaala didn’t want that answer. She rejected it, tried to negotiate. How about a liver transplant? No, she was told. She’s too unwell.

Another penny-dropping moment came when she asked doctors how many tumours there were.

“We didn’t count them, but more than 30 and less than 100.’’

Sinead, named for feisty Irish singer Sinead O’Connor, whose 2000 album Faith and Courage had blasted through the house as her mother and father painted the walls in a last-minute nesting frenzy before she was born, began chemotherapy in mid-October.

Three weeks on, one week off, three weeks on. Around them, the election campaign ramped up.

Jeff took leave from his job at Ballarat City Council and Jaala worked on the campaign when she could.

Sinead came home to Ballarat. Fridays were chemotherapy days in Melbourne.

Sometimes her temperature soared and she needed to be taken to the Ballarat Hospital. Other times, she vomited up her gastric nasal tube, and more hospital trips were needed.

But still it wasn’t clear how sick she was; how fast the cancer was moving inside her.

Jaala stayed in touch with the election campaign. She worked on Labor’s digital strategy, staying up late into the night. Many of those nights were spent on couches in Sinead’s hospital room or beside her daughter’s bed at home.

Every second night she alternated with Jeff on hospital duty — “a juggle but it was a manageable juggle’’.

The escape into the parallel world of politics was welcome. In those first four weeks, few beyond family and friends knew Jaala was running her campaign from a hospital ward. She did media interviews. Wrote and delivered speeches. Met stakeholders. Loved and cared for her sick little girl.

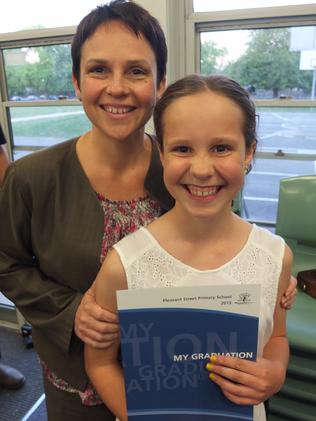

Sinead was determined to be out of hospital for her 13th birthday on October 20. “Everyone made a great effort to make that happen,” Jaala says.

She was getting sicker, but the family still expected she had up to a year to live. They thought it was the chemotherapy’s toxic effects that were making her sleep all day and be too ill to hold her medication down. They were hopeful, but starting to acknowledge that just maybe, their little girl had only nine or 12 months left.

Polling day came on November 29 and Labor won. Jaala Pulford was part of a government instead of an opposition. She was ecstatic. She went home to hang out with her family.

On Tuesday, two days after the election, Sinead underwent a second scan to gauge the success of the chemo. The results were due on Friday. It was a big week.

“Wednesday we had the Caucus meeting and I was elected by my colleagues to be the Deputy Leader in the (Legislative) Council and on the front bench. That was really exceptionally exciting,’’ Jaala says. She ate a quick lunch with some colleagues and drove home to find Sinead very unwell.

Her two carefully compartmentalised lives crashed as Government House called and inquired how many seats she wanted at the next day’s swearing-in ceremony. “I said three but maybe four, but probably not four,’’ she says. A friend came to sit with Sinead while Jeff and Hamish rushed out of the house to get haircuts and buy new clothes for the swearing-in ceremony.

Jeff’s parents came to the house early the next day to look after Sinead while the Pulfords went to the swearing-in, one of only a handful of occasions where Jeff or Jaala wasn’t with her.

“Wednesday night I spoke to the Premier about my portfolios. My dream job. Then we go to Government House. Everyone is so excited,’’ Jaala says.

“That was the day we found out (former Labor minister) Lynne Kosky died. So it’s bittersweet.’’

Jaala — now the state’s new Agriculture Minister — attended her first briefings with senior staff.

Later, she took a call from Jeff reporting Sinead’s temperature was high and they’d head to Ballarat Hospital just to be safe. “Crushing, jarring, drag back to my other world reality,’’ Jaala recalls of that moment.

In her new office, the department secretary ran her through the agriculture portfolio. Handed a massive pile of papers, she can’t wait to read them.

“It’s very, very exciting but I’m very worried about what’s going on at home.’’

The next day, Friday, Sinead is too unwell to travel to Melbourne, so Jeff stays with her in Ballarat and Jaala goes alone to the RCH to meet with an oncologist for the latest test results.

It’s devastating news. Sinead’s body is riddled with tumours. The cancer has not been defeated by the chemotherapy. Their little girl is sicker than they dared imagine.

“I’m not thinking it’s going to be a week away. No way. No way. I’d banked until September in my mind and Jeff had banked until June. And we’d planned to take her to the Port Fairy Folk Festival. My sister bought these amazing tickets to Cirque de Soleil, which was not until February.”

Reeling, Jaala goes back to work, and somehow, has another briefing. That famous steel shows as she straps in for discussions about policy priorities, funding and frameworks. Then she drives up the highway to spend the night with her girl at the Ballarat Hospital.

She tries to read her briefing notes but Sinead is unwell all night and nothing gets read.

Saturday, December 6, and the Ballarat Hospice doctor came into their room saying: “good morning Sinead, how are you?”

“My assertive little patient declares ‘I want to go home.’ Jaala says.

The doctor wants to keep her in for 24 hours but Sinead insists. The doctor agrees, but first he wants to speak to Jaala outside.

They got to a play area off the corridor, surrounded by old toys.

Jaala cries, and stumbles her way through the hardest question of her life. How long does her girl have? Is it days? “Yes it’s days. You need to take her home now so she can die.”

She calls Jeff and tells him to come to the hospital. She needs him. They need each other. She remembers that she’s the new Agriculture Minister and feels a flash of worry for the responsibility.

She calls a colleague and asks them to ask the Premier for leave from her job. “I had a text from Daniel within minutes saying something like ‘don’t worry about work, put your family first, do what you have to do, we will be here for you when you get back.’

Sinead went home on the Saturday afternoon. On Sunday, friends and family moved in. Mattresses appeared on the floor. Dozens more people came to visit. Jeff and Jaala slept in Sinead’s bedroom on a stretcher. The palliative care nurses were calm and caring. The house was filled with love. “Sinead’s friends came. 13 year-olds all through the house all that week. It was so great. It was really, really beautiful,’’ Jaala says.

On Thursday, palliative care nurse David came in the morning and again at 9pm. He said: “If there’s anyone that she needs to see you need to get them here now because it might be 12 hours but it’s almost certainly not more than 36.’’

Sinead is lucid, with her mental faculties at full capacity. She sleeps a lot but talks and corrects people if they’re wrong, until just three hours before she died. She has someone by her bedside at every minute of the day and night.

The family has drawn up a sleeping roster and a wrecked Jaala is ordered to bed at 3am on Friday, December 12. Her brother and sister-in-law insist she try to sleep, saying “we’ve got this.’’

She collapses into the little stretcher at the end of Sinead’s bed. After 5am, they wake her.

Sinead’s breathing has changed. She has literally seconds to get to her little girl’s side.

“I stumbled the two or three steps to her bed and held her hand and told her how much we loved her and I told her that we’d do all the things we’d talked about doing together without her. And she gave me a final hand squeeze and she took her last breath and then she was gone.’’

Sinead had her mother’s big grin, her dad’s sandy hair, and a personality as large and bright as a circus big-top.

One of the first things she learned to say as a toddler was “Nadie do it.’’

She wanted to do it — whatever it was — without help.

When she was given a unicycle at the age of nine, she decided to master it by herself.

Ignoring parental demands to take it outside, she learned to balance on the one-wheeled bike by crashing up and down the hallway in the family home. The walls still carry the scuff marks. Jaala and Jeff doubt they’ll ever be able to paint them over.

She played netball, she surfed. She never stopped talking. She loved her iPad, and reading late into the night. Her mother would get emails indicating Sinead was buying ebooks at midnight. She was a loyal friend. “We had a good sense of the person she was becoming,’’ her mum remembers.

“When we talked to her about her dying, she said: ‘does this mean I won’t have a normal life?’’

“She knew exactly what was going on. She said she wanted to go to university. She was angry she couldn’t do that.

“She wanted to go travelling and have a family and all those things that kids want to be able to get to do when they get big.”

That Friday morning, the household mourns, then leaps into action. Jaala’s mum makes endless cups of sweet, milky tea. Two others leave the house and vow not to return until they’ve found the perfect venue for Sinead’s funeral, which will be named a memorial party. Jeff and Jaala sit quietly with their beautiful girl for a while before she is taken away.

“We planned a celebration of her life. We decided to throw out the rule book of what a funeral should look like. We had everybody wear yellow (Sinead’s favourite colour). One of my oldest friends put yellow curling ribbon around Daniel Andrews and John Brumby. She said they didn’t have enough yellow on.

“We had a photo booth and a lot of loud music. All her favourite food. There were three 13-year-olds who spoke. They stole the show.’’

The memorial party was held at Sinead’s school on December 18.

There was champagne and helium balloons and pop music. There was a unicyclist.

Jaala’s old union friends turned up with high-vis yellow vests in case anyone dared to attend without wearing yellow.

It was beautiful, and joyous and very, very sad, all at the same time.

Sinead’s friends had started a hashtag. #angelsholdsp first appeared at 5.15am the morning after she died, when a group of teens set their alarms, wrote the message on their wrists, photographed it and posted it to their social media accounts. It lives on now, out there in cyber-space.

Jaala went back to work on January 6. She is raw, but resolute.

She agrees to this interview to acknowledge that the loss of her daughter is something that will always be a part of her. Anyway, Sinead would have insisted her mother get on with it.

“Sinead embraced life fully and she made it very, very clear to us that she expected us to do the same,’’ she says.

“Everyone grieves in their own way. We’ve been dealing with the loss not of our girl but our aspirations for our girl for a while now, since September.

“I understand this is something people might want to understand a little better.’’

On the wall outside Jaala’s office are photo boards featuring all 49 of Victoria’s Agriculture Ministers dating back to J.J Casey in 1872. All of them are men. Until now.

“I’m going to give this new role everything I’ve got. I want people to understand that this loss is just now part of me, something I will have to live with always — not just me, but everyone who loved her,’’ Jaala says.

“I accept that because of the extraordinary circumstances of becoming a minister then taking leave immediately … I feel like I’d like to provide an explanation because I think there are questions people could reasonably have about that.’’

Jaala, who grew up a country kid at Castlemaine and represented regional food industry workers at the union, is determined to work for country people now, in her new job.

“Those people deserve a strong champion and effective advocate and I am absolutely determined to take a “Nadie do it’’ type approach to this,’’ she says.

“She was a really good kid. She was smart, a good person, very decent.

“She died as she lived. She died on her terms.”

Article is republished courtesy of Herald Sun and Jaala Pulford.